Apple Zero-Day Risk: What You Should Know

Hoplon InfoSec

12 Feb, 2026

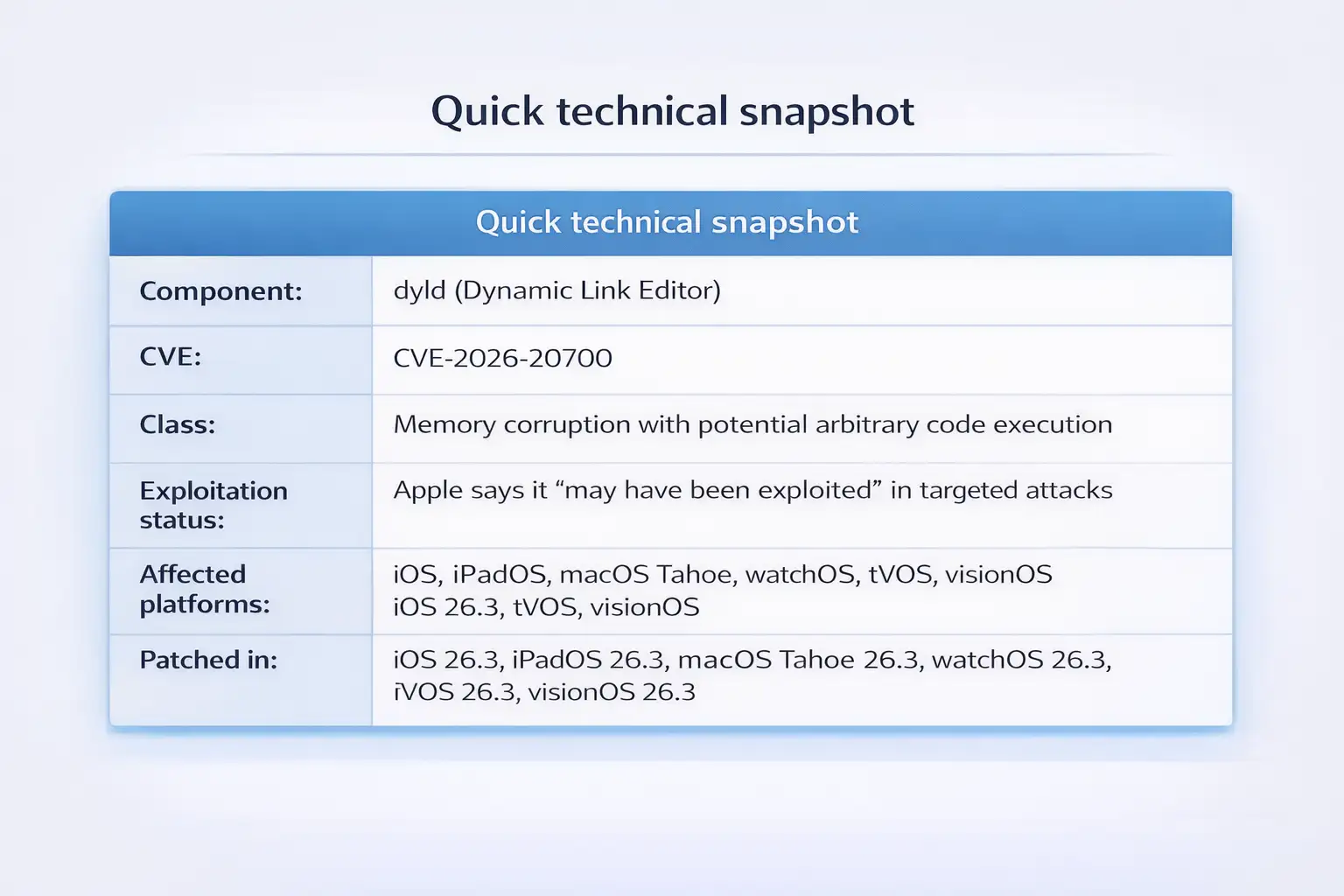

In the latest round of Apple security updates released on February 11, 2026, Apple confirmed that a vulnerability in dyld was exploited in an “extremely sophisticated attack” against targeted individuals. The issue, tracked as CVE-2026-20700, affects iOS, iPadOS, macOS Tahoe, tvOS, watchOS, and visionOS.

That single sentence from a security note is easy to skim past. But it carries a lot of meaning: “zero-day,” “exploited,” “sophisticated,” “targeted.” If you manage Apple devices in an enterprise, teach security, or investigate incidents, those words should trigger a different kind of attention than a normal patch cycle.

This guide breaks down the Apple zero-day vulnerability concept using this February 2026 dyld case as a real anchor. You’ll learn how Apple zero-days tend to be found and abused, what “in the wild” usually implies, how exploit chains work on modern iOS and macOS, and what to do right now if you’re responsible for a fleet of iPhones, Macs, or Apple Watch devices. Along the way, I’ll call out the places where public details are intentionally limited, and why that matters for defenders.

What happened

Apple released iOS 26.3, iPadOS 26.3, macOS Tahoe 26.3, tvOS 26.3, watchOS 26.3, and visionOS 26.3 to address multiple issues, including an actively exploited vulnerability in dyld (Dynamic Link Editor), tracked as CVE-2026-20700. Apple notes the bug “may have been exploited” in an “extremely sophisticated attack” against “specific targeted individuals” on iOS versions before iOS 26.

Independent reporting confirms the same framing and highlights that dyld is a core component across Apple platforms, which is why the fix spans so many operating systems.

One more detail in Apple’s notes matters for defenders: Apple references two earlier WebKit zero-days, CVE-2025-14174 and CVE-2025-43529. That does not prove a specific chain, but it strongly suggests this dyld issue may sit in a broader investigation where multiple bugs were relevant.

Why it matters

Zero-days matter because they flip the normal defender advantage. When a flaw is unknown or unpatched, your best routine controls do not fully apply. Patch dashboards look fine until they don’t. Signatures are often late. And for some classes of attacks, there may be little to detect until the attacker is already done.

With Apple devices, the stakes are unusually high because they are often “identity hubs.” One phone can hold corporate email, SSO sessions, password manager access, MFA prompts, VPN profiles, and years of messages. A targeted compromise can become an identity incident even if the attacker never touches a laptop.

Also, Apple’s wording is deliberate. When Apple uses language like “extremely sophisticated” and “targeted individuals,” it usually signals a real, high-effort operation, not a mass campaign. That’s not a reason to panic. It’s a reason to patch quickly and harden the people most likely to be targeted first.

What Is Apple zero-day vulnerability?

An Apple zero-day vulnerability is a security flaw in Apple software or firmware that is exploited before the vendor has broadly deployed a patch, or before defenders have had reasonable time to mitigate. In plain terms, an Apple zero-day vulnerability is the kind of bug defenders are racing to understand while attackers are already using it.

“Zero-day” is about timing and asymmetry, not automatically about severity. Some zero-days are devastating on their own. Others only become dangerous when paired with a second weakness. On modern Apple platforms, the highest-impact attacks often involve multiple steps, sometimes called an exploit chain: a browser bug to get a foothold, then a sandbox escape, then a privilege gain, then actions like surveillance or data theft.

If you want a clean definition from a research firm perspective, Mandiant frames it this way: a zero-day is “a vulnerability that was exploited in the wild before a patch was made publicly available.”

Background: why Apple platforms get targeted

Apple devices are strong by default, especially iOS. Sandboxing, code signing, and hardware-backed protections raise the bar. Ironically, that strength can increase attacker interest, because a working exploit becomes rare and valuable.

There’s also a social reality that matters. High-value individuals often prefer iPhones and MacBooks, and those devices carry the most sensitive conversations. If an attacker can read one person’s messages or harvest one person’s tokens, that can be worth far more than infecting thousands of random users.

Where it is used

When people say “Apple zero-day,” they’re usually talking about:

· iPhone and iPad exploitation via iOS and iPadOS

· Mac exploitation via macOS

· Browser exploitation via Safari and WebKit, which underpins browsers on iOS

· Cross-device exposure where the same component exists across Apple operating systems, as with dyld in this case

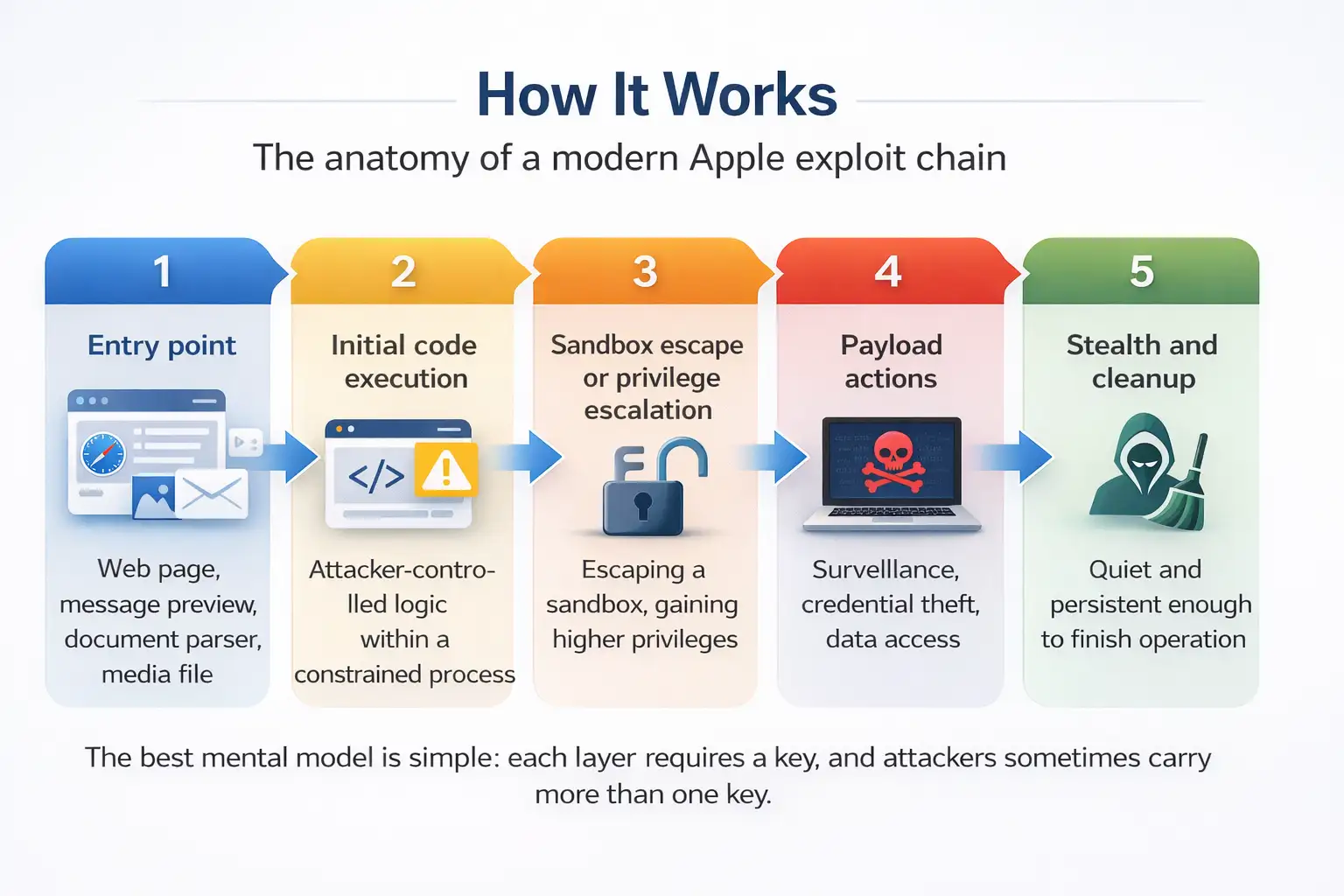

How It Works

The anatomy of a modern Apple exploit chain

Modern Apple security is layered. That’s good news, but it shapes how attackers operate. A common pattern looks like this:

1. Entry point

Often a web page, a message preview, a document parser, or a media file. WebKit is frequently involved because it processes untrusted content at internet scale, and it is a repeated historical target.

2. Initial code execution

The attacker gets the device to execute attacker-controlled logic, often inside a constrained process like a browser renderer.

3. Sandbox escape or privilege escalation

To do meaningful harm, attackers need to cross boundaries. That might mean escaping a sandbox, gaining higher privileges, or gaining a primitive like reliable memory writing.

4. Payload actions

This can be surveillance, credential theft, data access, or movement into corporate systems via accounts and sessions.

5. Stealth and cleanup

Targeted attacks try to stay quiet. Not always “persistent forever,” but quiet enough to finish the job.

The best mental model is simple: each layer requires a key, and attackers sometimes carry more than one key.

Where dyld fits in (and why defenders should care)

dyld, the Dynamic Link Editor, is responsible for loading dynamic libraries and linking them to applications at runtime. In human terms, it’s the backstage crew that sets the scene before the app runs.

Because dyld sits in a critical path across Apple platforms, a flaw there can be attractive in later stages of an exploit chain. Apple describes CVE-2026-20700 as a memory corruption issue where an attacker with “memory write capability” may be able to execute arbitrary code.

That “memory write capability” phrase is doing a lot of work. It implies dyld might not be the first domino. Attackers often need an earlier bug to gain the ability to manipulate memory reliably, and then a later bug helps them turn that capability into code execution or deeper control.

For defenders, that wording should trigger a practical inference: assume chaining is plausible, and treat patching as urgent even if the public story feels incomplete.

Key terms, without the fog

· Memory corruption: software mishandles memory, causing crashes or enabling controlled changes to program behavior.

· Arbitrary code execution: the attacker can run code of their choosing, not just trigger a crash.

· Sandbox: a boundary that limits what a process can access.

· Exploit chain: multiple vulnerabilities used together to reach a goal.

If you manage security comms internally, this is the vocabulary that helps non-specialists understand why a “single bug” can still be serious.

Apple zero-day vulnerability: What happened in February 2026?

Apple’s advisories state that CVE-2026-20700 affects iOS 26.3 and iPadOS 26.3, macOS Tahoe 26.3, watchOS 26.3, tvOS 26.3, and visionOS 26.3. Apple acknowledges a report that it may have been exploited in extremely sophisticated attacks targeting specific individuals on iOS versions before iOS 26.

Apple also reiterates its standard practice: it typically avoids discussing or confirming details until an investigation is complete and patches are available. This helps reduce risk while updates roll out, but it also means defenders should avoid filling gaps with speculation.

Some commentary in the wider ecosystem tries to jump straight to “spyware” narratives. It is fair to say that targeted, sophisticated exploit chains have historically been used in spyware-style operations, and Apple’s references to past WebKit issues suggest chain thinking is reasonable.

Quick technical

Real-world example: a realistic attack scenario

Picture a senior finance executive who travels constantly and lives out of their phone. They use Safari to open links from calendar invites, airline updates, and investor emails. They also use corporate SSO on the device and approve MFA prompts on the go.

A targeted attacker does not need a loud campaign. They can craft one believable lure, aim it at one person, and patiently wait. A malicious website might trigger a browser flaw to gain initial code execution in a restricted process. Next, a second vulnerability could allow the attacker to write into memory or break out of the sandbox A bad website might use a bug in a browser to run code for the first time in a small way. Then, a second flaw could let the attacker write to memory or leave the sandbox.

Finally, a dyld issue like CVE-2026-20700 could help turn that foothold into code execution in a more powerful context.

The end goal is often narrower than people assume. Sometimes it’s not “own the device forever.” Sometimes it’s “read messages for two weeks,” “pull a token,” or “watch location movement during a negotiation.” Quiet operations are hard because they are designed to look like nothing happened.

Impact analysis: who is most at risk

Individuals

Most people are unlikely to be individually targeted by an “extremely sophisticated” exploit. Still, patches matter because techniques spread. Pieces of once-rare exploitation sometimes get repurposed, independently rediscovered, or quietly sold.

Higher-risk groups often include:

· Journalists and activists

· Executives and board members

· Government officials and staff

· People in sensitive legal cases or negotiations

If you’re in one of those categories, “targeted individuals” is not abstract language. It’s a practical risk label.

Organizations and industries

If your organization relies on iPhones for authentication, Macs for development, or Apple devices for executive communications, one compromised device can become a credential and access incident.

Industries with outsized exposure tend to be:

· Finance and fintech

· Healthcare leadership and research

· Government and defense-adjacent orgs

· Media organizations

· IP-heavy tech companies

The reason is simple: the people and data are high-value, and the device is the easiest bridge between them.

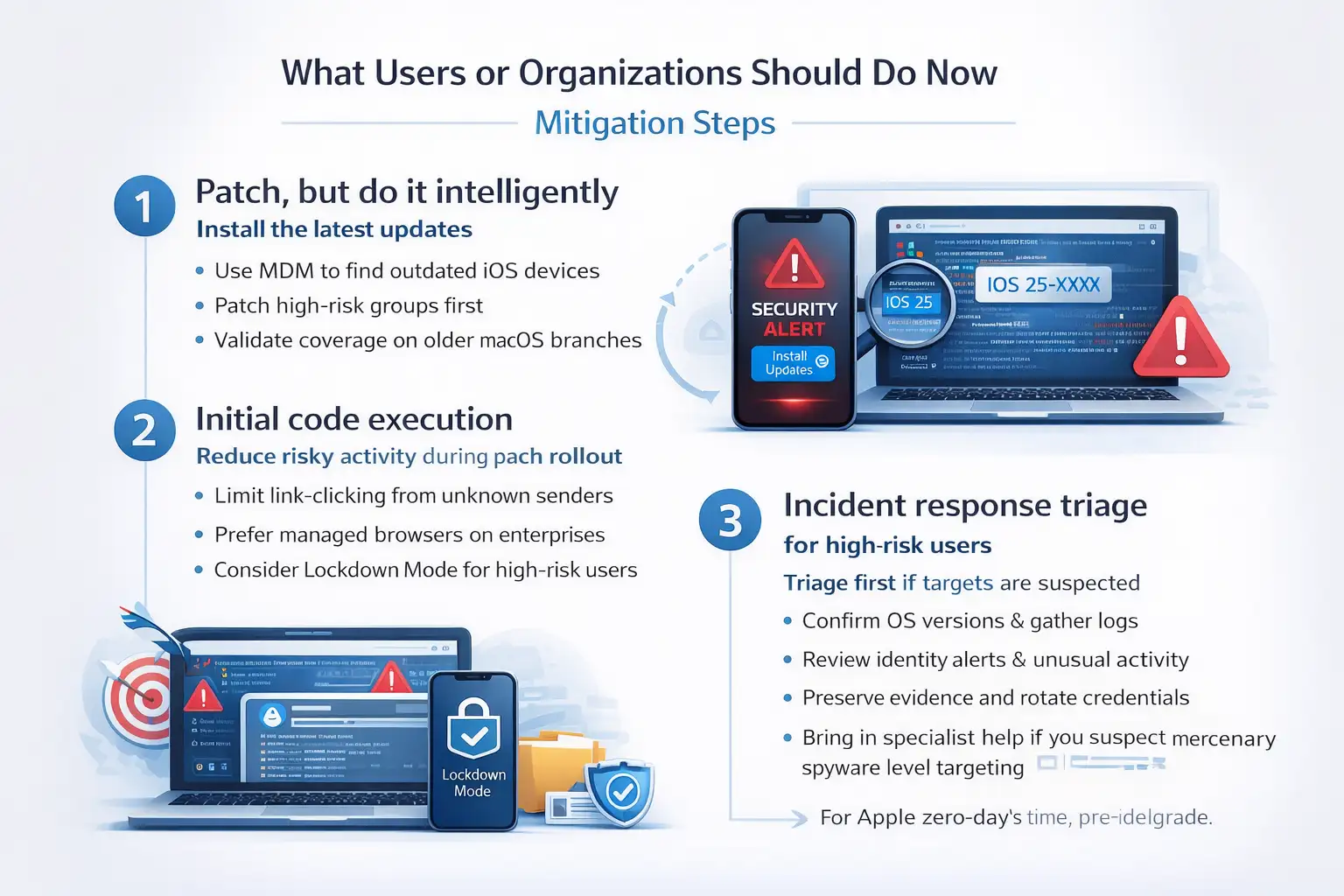

What users or organizations should do now (mitigation steps)

Step 1: Patch, but do it intelligently

Apple’s guidance is clear: install the latest updates. For Apple zero-day vulnerability situations, speed matters more than perfect scheduling, especially for high-risk users.

For enterprises, “intelligent” means visibility and prioritization:

· Use MDM to find devices on iOS versions before iOS 26, then prioritize those users first.

· Patch high-risk groups on day one, not day ten.

· Validate macOS Tahoe coverage and track older supported branches if Apple issued parallel fixes for them.

A practical rule that holds up in real life: if it’s exploited, patch latency becomes your enemy, not the vulnerability alone.

Step 2: Reduce exposure while patches roll out

Sometimes patching every device immediately is not realistic. If you’re in that window, reduce risk where attacks often begin:

· Limit link-clicking from unknown senders, especially on high-risk devices.

· Prefer managed browsers and device policies where feasible.

· Reduce unnecessary browser extensions on macOS.

· For people with credible targeted risk, consider Lockdown Mode, understanding the tradeoffs (it restricts functionality and has management implications).

Lockdown Mode is not for everyone, but it exists for a reason: it reduces attack surface for sophisticated chains. Google has publicly noted that Lockdown Mode has helped prevent exploitation of some in-the-wild chains in past years.

Step 3: Incident response triage for high-risk users

If you suspect someone may have been targeted, treat it as a serious incident even if you lack obvious indicators.

Practical triage steps:

· Confirm OS versions and update history for the device.

· Review identity signals: new device logins, unusual token refreshes, unexpected MFA prompts.

· Preserve evidence before wiping if you can, especially for high-risk roles.

· Rotate credentials tied to the device (email, SSO, VPN, developer accounts).

· Bring in specialist help if you suspect mercenary spyware level targeting.

One caution from the field: wiping too fast can destroy the timeline you need to understand what happened.

Why it matters in cybersecurity

The bigger security lesson here isn’t just “patch faster.” It’s that modern exploitation is increasingly about chaining capabilities. Memory corruption is still a major theme in high-end exploitation, which is why Apple has invested heavily in mitigation approaches at the platform level.

From a defender’s perspective, the practical move is to treat Apple device security as a program, not an assumption. Programs have:

· Accurate inventories

· Patch SLAs for exploited issues

· High-risk user playbooks

· Strong identity monitoring and phishing-resistant MFA options

This is also where good communication matters. Decision-makers do better when you translate “memory corruption in dyld” into business language: “This is a targeted risk that can lead to account compromise and sensitive data exposure if devices are not updated quickly.”

Common misconceptions

Misconception 1: “Zero-day means everyone is infected.”

No. Zero-day means there was a period when attackers could exploit a flaw before defenders could patch. In this case, Apple’s language points to targeted exploitation, not mass compromise.

The correct takeaway is boring but powerful: patch quickly, prioritize high-risk users, and keep visibility on version drift.

Misconception 2: “If Apple doesn’t share exploit details, we can’t defend.”

Limited disclosure is frustrating, but it is still actionable. Apple’s advisories tell you the component, the impact class, the fixed versions, and whether exploitation is suspected. That is enough to drive prioritization and response.

Misconception 3: “We should wait for stability before patching.”

For normal bugfix updates, cautious staging can be reasonable. Waiting makes problems worse for those who are being exploited. The compromise is to roll out in phases with guardrails, not to delay without a plan.

More general lessons about security and what they mean for the future

This event from February 2026 is another example of a pattern that defenders see all the time: exploitation is rarely about just one bug.

Treat every Apple zero-day vulnerability as a likely piece of a chain until proven otherwise.

The long-term improvement is procedural:

· Shorten patch cycles for exploited issues.

· Maintain an executive protection playbook.

· Monitor identity events tied to mobile devices.

· Reduce browsing and content-processing exposure for the most targeted roles.

And a small personal opinion that comes from too many incident calls: the fragile point is often not the exploit. It’s the organization’s ability to respond quickly without confusion.

Hoplon Insight Box

1. Patch the people, not just the devices

Start with users who hold access, authority, or sensitive data. Executive iPhones and developer Macs should be on the shortest timeline.

2. Treat “in the wild” as a priority multiplier

Even if the impact description feels abstract, exploitation evidence changes urgency. CVE-2026-20700 is a clean example.

3. Make browser surfaces boring for high-risk users

WebKit is a repeated entry point across incidents. Reduce unnecessary browsing and use managed policies where possible.

4. Build a high-risk user kit

A one-page checklist, a direct line to security, and a plan for rapid credential rotation if something looks off.

Conclusion

A well-run security program doesn’t chase every headline, but it takes exploited vulnerabilities seriously. The February 11, 2026 patches show why: a single Apple zero-day vulnerability in a core component like dyld can affect nearly the entire Apple ecosystem, and Apple’s own language signals real attackers already put it to use.

If you do one thing after reading this, make it effective and repeatable: verify device versions, patch quickly, prioritize high-risk users, and document your playbook for the next Apple zero-day vulnerability. That habit is what reduces risk over time.

FAQs (People Also Ask style)

1. What does “exploited in the wild” mean in Apple advisories?

It means Apple believes real attackers used the vulnerability outside a lab environment. Here, Apple says it “may have been exploited” in targeted attacks.

2. Which CVE is tied to the February 2026 dyld issue?

CVE-2026-20700.

3. Do I need to update if I’m not a high-profile target?

Yes. Even targeted exploits can become broader over time, and the update also fixes many non-zero-day issues.

4. Is this connected to WebKit zero-days from late 2025?

Apple’s notes reference CVE-2025-14174 and CVE-2025-43529 as related to the same report, but public details on any chain remain limited.

5. What should enterprises do first?

Use MDM reporting to identify vulnerable versions, prioritize high-risk roles, enforce patch deadlines, and monitor identity events tied to mobile access.

6. Does antivirus reliably detect this kind of attack?

Traditional endpoint tools often struggle with targeted exploitation. Patching, hardening, identity monitoring, and IR readiness usually provide more defensive value.

Share this :